Share this article

Four Intellectual Property experts outline the risks that arise in the legal arena regarding these types of innovations.

When does an AI creation receive legal protection? Does it matter whether the creation is human or artificial? These are some of the questions being raised in the world of advertising, branding, and patents, given the increasing use of generative AI in design and invention-related fields.

In fact, many of these organizations are already working on AI usage protocols and reviewing contracts to secure the intellectual property of their creations. In Chile, there is currently no legislation that requires brands to be created by human intelligence. “First of all, because the Industrial Property Law was enacted and has been modified in times when AI use still seemed distant in everyday contexts. And secondly, because the registration of a trademark focuses on the result (symbol, design, and sound), not on the creative process,” says José Ignacio Mercado, director of Carey’s Data Protection group.

Companies review their contracts to ensure intellectual property in the age of AI. In Chile, there is currently no legislation that requires brands to be created by human intelligence. The main questions revolve around whether AI can be recognized as an inventor and who is the true owner of an invention generated by AI—whether it is the creator of the AI system or the person who used it to generate a result. In the case of patents, the situation is different. “There, the trend is not to accept the patentability of inventions created by AI, and it has been determined that only natural persons can be considered inventors,” says Maximiliano Santa Cruz, partner at Santa Cruz IP, who mentions the example of Dabus, an AI system capable of generating inventions in various fields, leading its creator, Stephen Thaler, to submit patent applications in many jurisdictions.

“And, except in one country, all those applications have been rejected,” he says.

Doubts arise. Antonia Nudman, senior associate in AZ’s IP, Tech & Data group, adds that in the Dabus case, despite the jurisprudential consensus of prioritizing natural person status as a requirement for a patent inventor, “the use of AI systems is a reality in most patentable inventions, and this raises another discussion: What is the degree of human intervention necessary for industrial protection to be granted to the invention?”

“To address this, it is essential to foster coherence and balance between technological reality and preserving the importance and contribution of human ingenuity in the invention process,” she adds.

On this point, Mercado ensures that if an AI system is used during one of the stages of research or development that culminates in a potentially patentable invention, it is necessary to determine how and for what purpose the system was used. “First, as AI is trained, the results generated by the AI system could reveal that something is already part of the prior art and thus lack inventive level. Or, more dangerously for the inventor, it could load sensitive information, which could jeopardize the possibility of obtaining a patent on the result of their work or the chance to protect components that are not patentable through trade secret protection,” explained Carey’s lawyer.

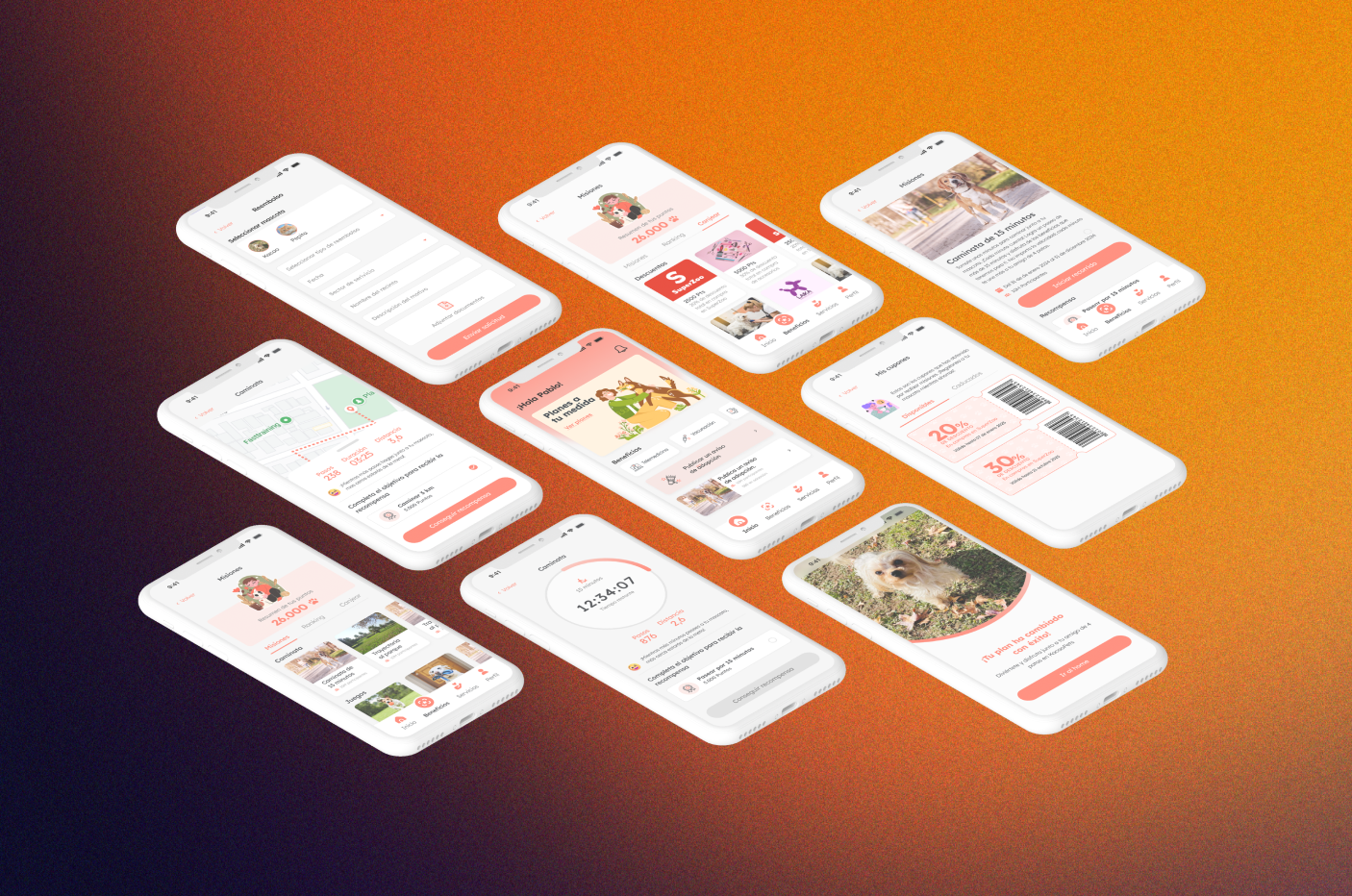

After overcoming these barriers, a brand created with AI or a patent developed with this technology, according to Santa Cruz, would have the same rights as any other brand or patent. This—he says—is because the laws, based on international treaties of which Chile is a part, do not discriminate between technical areas: “All brands are granted the right to prevent third parties from using them in commerce when there is a likelihood of confusion among consumers, for 10 renewable years. The same applies to a patent, which grants exclusive rights to its holder to use, manufacture, sell, offer for sale, and import the invention, or authorize a third party to do so, for 20 years from the application date.”

Outdated legislation Another key point is the legal doubts raised by these innovations. Rodrigo León, partner in the Data Protection, Technology, and Media area at Silva Abogados, argues that the ownership of rights, as well as the patent wording, can now be done through generative AI, leading to questions about whether it is legal to register patent claims not written by a human.

“Initially, this shouldn’t be possible, but in the future, this issue should start to be regulated,” he argues. Santa Cruz points out that the main questions are about the possibility of recognizing AI as an inventor and who is the true owner of an invention generated by AI—whether it is the creator of the AI system or the person who used the system to generate a result. There is also no consensus on how flexible brand legislation is regarding this challenge. While Santa Cruz considers it “very flexible,” León disagrees. “These laws have always thought of creations as the result of human creative activity, but in fact, these AI productions are not strictly human, so the challenge is greater and legislations will have to address the issue,” explains this expert.

Meanwhile, Mercado does not see brand legislation being directly impacted by AI, despite the points raised regarding the prior creative process related to the brand’s construction or how it is exploited or used. For León, the ethical use of these platforms emerges as one of the aspects that should be regulated in light of AI development. Mercado, on the other hand, warns that the major problem AI presents is that no one fully understands what it is or the risks involved in its use.