Share this article

Making more efficient use of time and increasing students’ motivation in class are some of the benefits reported by schools. However, national measurements are still lacking.

High school juniors from the Liceo Bicentenario Matilde Huici Navas in Peñalolén take out their phones and scan a QR code projected on the board. It’s a Natural Sciences class, where, through the Argumentapp application, they must solve a challenging question like “Are there good and bad foods?” and then present their ideas on a digital board, sharing their learning and arguments.

Students studying in front of a computer.

These types of educational experiences are becoming increasingly common in classrooms, driven by the strong growth of educational technologies.

“Each teacher has a session on the platform, where they create their classes. Students join using a QR code, not only from a tablet but also from their own phones. It’s important that the questions we pose generate discussion,” explains teacher Claudia Araya. She adds, “I think it’s good for cell phones to be incorporated as part of the classroom strategy rather than always being seen as something negative.”

These educational experiences are becoming increasingly frequent in classrooms, paralleling the significant growth of educational technologies — commonly referred to as “EdTech” — not only in Latin America but also in Chile.

A report from Innspiral, an innovation accelerator, shows that in Chile, the number of EdTech companies has grown from 66 to 166 over the last 10 years. In Latin America, the growth has been from 704 to 2,488 — a threefold increase.

According to Camila Mohr, general manager of Innspiral, the increase in these technologies in Chile is due to the country’s educational challenges. “If we look at the 2022 PISA study, our results are far below the OECD average,” she says. She adds, “While EdTech won’t solve the problem, it complements classroom education.”

However, she also points out the lack of empirical evidence about the true impact of these technologies on improving learning outcomes. “There are 500,000 educational apps. It’s a massive universe. Who certifies that I will learn correctly with them? That doesn’t exist. There’s a need for collaboration to create international-level certifications,” she explains.

In schools like El Mirador in Puente Alto and San Fernando in Peñalolén, part of the Feduca network, technologies are also integrated as a core part of their educational projects. One example is Swarmob, a digital platform for implementing Project-Based Learning (PBL). On the one hand, it allows collaboration among teachers to plan interdisciplinary challenges addressing social and environmental issues aligned with the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals. On the other hand, it connects projects across different regions. For instance, students in Chile working on projects to solve the scarcity of potable water can exchange ideas with peers in Mexico and learn about their realities.

Rodrigo Bosch, founder of the Feduca network, says that using EdTech increases student motivation since digital language resonates more with them. However, he believes it’s “not a silver bullet. Platforms help, but schools need to learn from these processes, evaluate the impact, analyze data, and make decisions based on what’s working and what isn’t.”

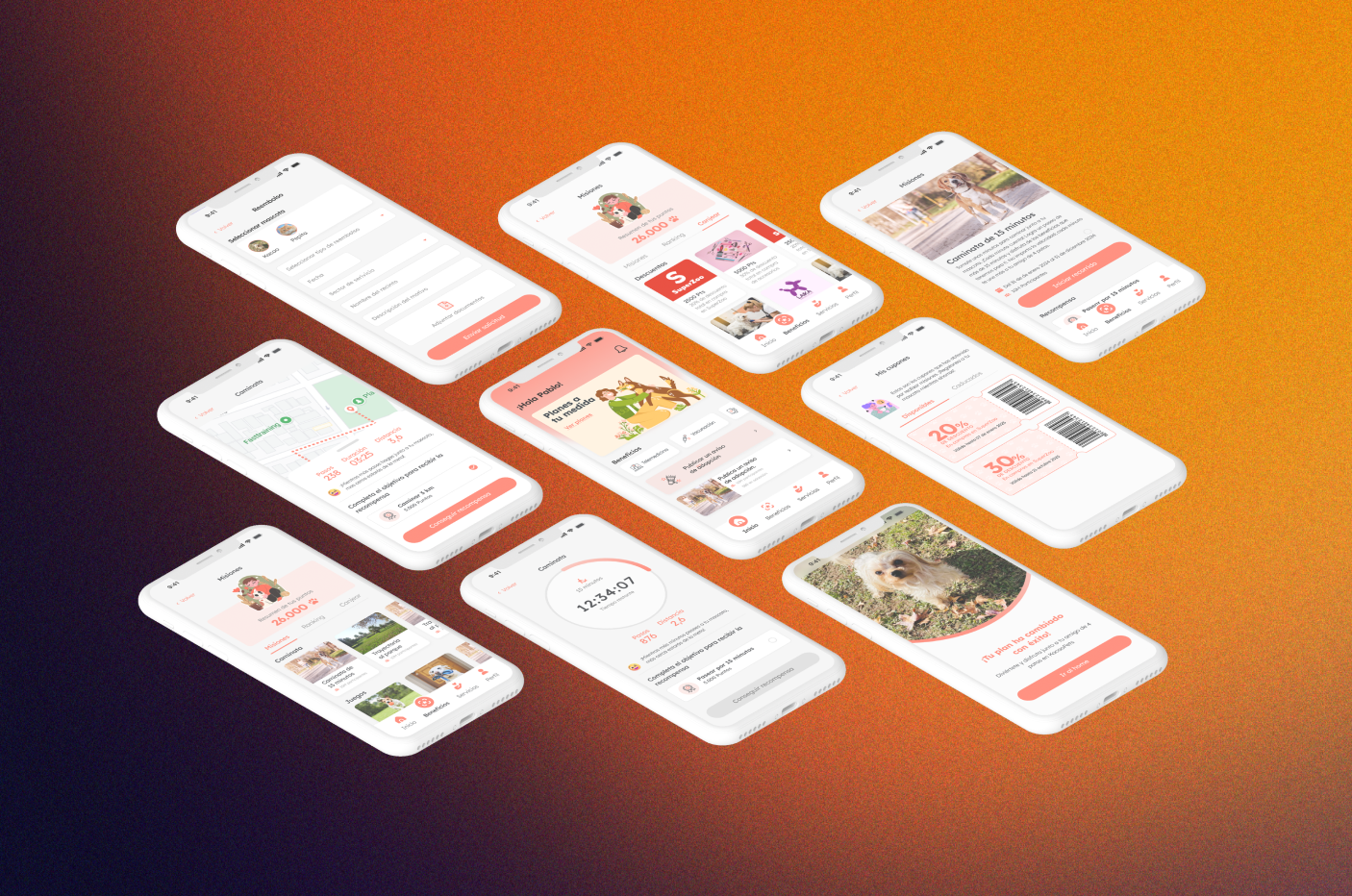

Camila Espinoza, academic coordinator at Betterland School in Lo Barnechea, explains why they have adopted such technologies, in their case, Ummia, for class planning. “One of the tasks that consumes the most time for teachers outside the classroom is class preparation and planning.” She highlights, “Using a platform with artificial intelligence (AI) helps optimize time. Of course, the teacher must adjust and build upon the AI’s proposal, but it provides an initial draft to work from, which speeds up the initial creation process,” she concludes.